Repetition Without Repeating Yourself

Geek-o-meter: 1️⃣ 2 3

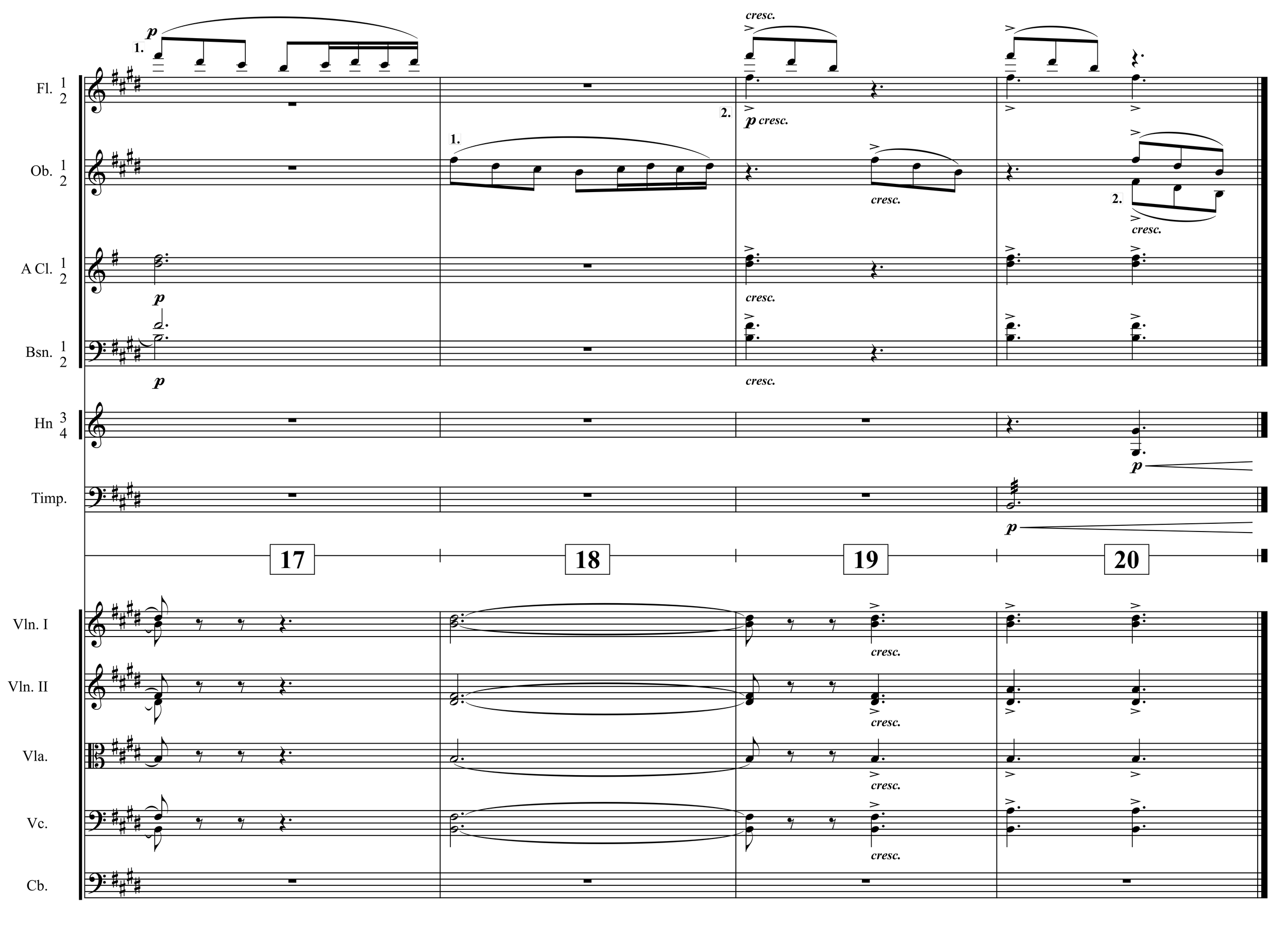

(Morning Mood, Part 2: Bars 5–20)

In the previous post, we looked at the opening of Grieg’s Morning Mood and how the magic came not from adding layers, but from removing them. The viola transition got a moment in the sun – because someone else stepped aside.

In this follow-up, we’ll dive into bars 5–20 and watch how Grieg builds without ever cluttering. The orchestration grows, yes – but mostly by reusing, reshaping, and rebalancing familiar materials. If you missed the first post, you’ll want to read it. If you didn’t miss it – welcome back.

Before we get into the details, do yourself a favor: open the score (if you have it), hit play on this video, and follow along from bar 5:

🎧 Grieg – Morning Mood (YouTube)

You’ll hear what we’re about to unpack – the contrast by spacing, the repetition without boredom, and that glorious little orchestration trick Grieg pulls in bar 20. Let’s get into it.

Bars 5–8: Same Register, New Contrast

(How dynamic and timbral separation keeps the oboe in the spotlight)

Bars 5–8 continue the phrase but change the game. Harmonically, we get a slight shift at the cadence, and the dynamic peak moves half a bar later. That alone gives the phrase a different shape. But let’s talk orchestration.

Unlike bars 1–4, we no longer have register contrast between melody and accompaniment. The oboe now carries the tune, and its notes often overlap with the first violins – sometimes even landing directly on the same pitches. But Grieg makes sure the oboe still stands out. How?

Two much clearer types of contrast are at play here:

1. Dynamic contrast: the oboe is marked one dynamic level louder than the strings. It’s subtle, but enough to tilt the balance.

2. Instrumental contrast: most importantly, the melody is now played by a different orchestral choir. The oboe isn’t a string instrument. Even when it shares the register, its color cuts through.

These two factors – louder and different – give us clarity even when the notes collide.

But look closely at bar 8. Remember how, in bar 4, the woodwinds dropped out just before the strings entered, creating space for the viola bridge? (See earlier post.) Now that gesture is missing – the strings don’t pause this time. They just keep going. So what happens?

The bassoon line gets swallowed.

Despite having a unique timbre and being marked louder, it sits between 2–3 string voices above and below. There’s no air around it. The line is audible, but the balance is different.

It’s a brilliant contrast to bars 1–4. There, Grieg created space by stepping aside. Here, he lets things blend – not chaotically, but densely. It’s orchestrated weight. And it sets us up for the next shift in texture.

Bars 9–16: Same Melody, Different Light

(Why Grieg doesn’t change the orchestration – and why it still sounds new)

Bars 9–12 are an exact orchestration copy of bars 1–4. And bars 13–16 copy bars 5–8, note for note. But listen again: the instruments don’t sound the same. The whole thing is now a third higher, and that changes the sonority ever so slightly.

What’s clever here is that Grieg doesn’t change the orchestration, even though the harmony has changed. The melody is the same, but the chord progression beneath it has shifted. So why keep the orchestration identical?

Because nothing feels familiar yet.

This is the listener’s first chance to recognize the material. It’s the repetition – not the variation – that creates engagement. Grieg gives us something to hold onto. Only once it’s been stated twice does he start to reshape it.

The contrast in these bars comes from harmony and register, not from rewriting the arrangement. It’s a gentle way of saying: “You’ve heard this before – now listen again, slightly differently.”

Bars 17–20: When Two Worlds Collide

(Combining textures for maximum payoff – with nothing but what’s already on the page)

So far, we’ve heard the same 4-bar melody four times:

– once high in the flute, accompanied by woodwinds,

– once low in the oboe, accompanied by strings,

– then both of those versions repeated a third higher.

Now Grieg takes us up yet another third and lands us squarely on the dominant of the home key. But this time, the melody isn’t played in full. It’s fragmented, delivered one bar at a time – and Grieg does it using the exact same orchestration logic we’ve already learned to trust.

Bar 17: flute + woodwind accompaniment.

Bar 18: oboe + string accompaniment.

Bar 19: same structure, but the switches happen every half bar.

And bar 20? That’s the payoff.

Suddenly both flutes and oboes play – 2nd flute expands the woodwind chord with an upper octave above the 1st bassoon, while 2nd oboe fills in a lower octave beneath the 1st oboe melody. At the same time, both the strings and the woodwinds join forces as accompaniment. It’s the same two orchestration worlds we’ve been toggling between – now finally combined.

Add a timpani roll. Add a soft dominant push from horns 3 and 4. You’ve just orchestrated a build-up that feels inevitable, elegant, and emotionally charged – using nothing but the materials already on the page.

What’s especially brilliant is how Grieg gets more impact not by writing new material, but by combining what’s already there. First we get four bars of woodwinds. Then four bars of strings. And then – four bars where both play together. It’s 1 + 1 = 3. The combination feels fresh and climactic, even though nothing is new. He’s not inventing another layer or writing four more bars of material. He’s just playing mix-and-match with elements we already know – and that familiarity is what gives the climax its weight.

This is orchestration that grows without bloating.

It escalates without ever shouting.

And it lands exactly where it should.

Take This to Your Next Score

In the next post, we’ll look at how this carefully constructed build-up leads into the climax at bar 21 – where Grieg finally lets go a little. It’s the payoff to everything we’ve heard so far: the spacing, the contrast, the layering. But for now, this is a good place to pause. Because before you can orchestrate a great climax, you need to know how to earn it. And that’s exactly what bars 5–20 do.

If you’re studying orchestration, there’s a lot to steal here – gently, of course. Learn to spot where contrast comes from: not just instrumentation, but register, dynamics, and pacing. Notice how Grieg reuses material instead of constantly inventing new layers. Notice how doubling doesn’t have to be obvious, how fragments can still feel like full ideas, and how combining familiar textures can sound like something new.

In your own work, start asking:

– Can I get contrast without changing instruments?

– Can I reuse a texture instead of writing a new one?

– Can I combine two simple things to create a third?

And next time you study a score – whether it’s Grieg or Goldsmith – look for the moments where the orchestration isn’t flashy, but simply right. That’s the kind of quiet craft this music teaches best.